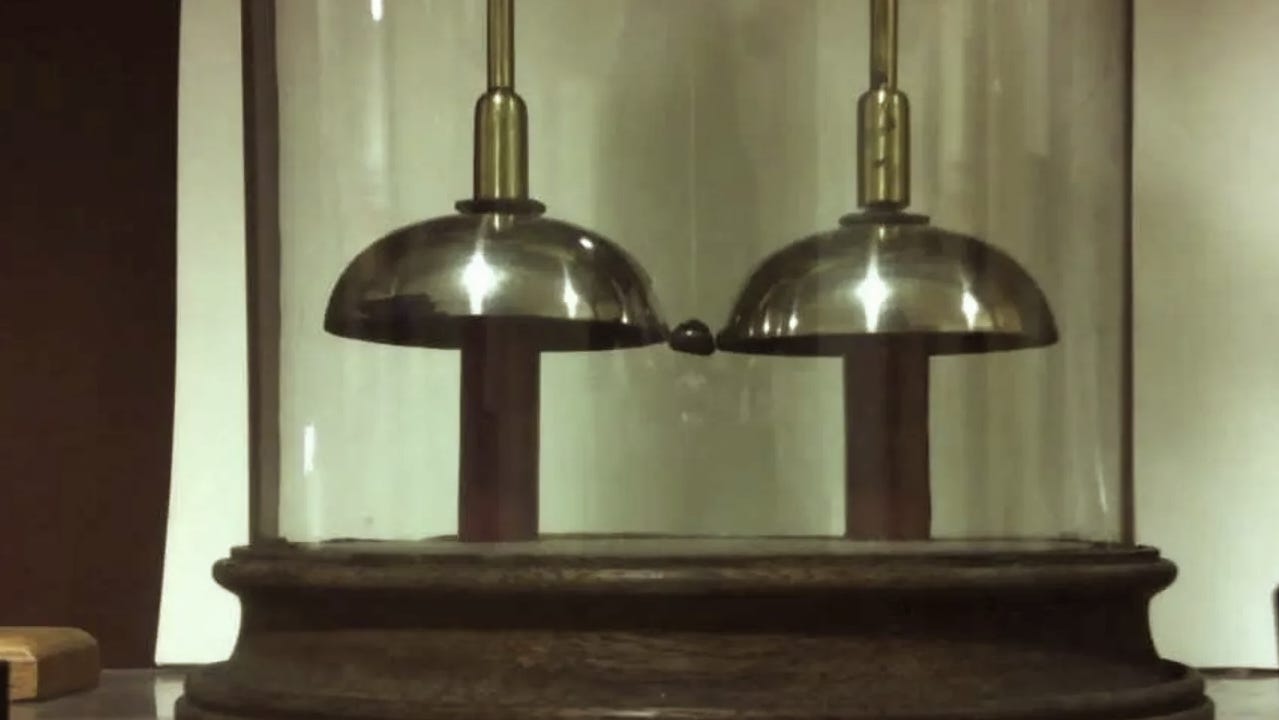

There’s this electric bell at Oxford University.

It’s creatively called the Oxford Electric Bell.

Been sitting there for like 180 years. Behind a glass case so you can’t hear it, but know that it chimes two times every second.

172,800 times a day.

More than 15 billion dings over the nearly 200 years it’s been, well, dinging.

Like the world’s worst battery-low smoke detector

The thing about the Oxford Electric Bell is that while it’s been about as consistent as anything else in the world over this stretch of time, there’s just one small issue.

No one is exactly sure what’s keeping it ringing.

I mean, they kind of know. The basic working understanding is that, in technical terms, it’s running off a Zamboni dry pile (an early form of battery), stacks of metal, and other things (like paper) producing electromagnetic charges.

That’s the thinking, at least.

No one wants to open it to find out for sure, because it might make the OEB stop ringing. And that would be bad.

From what I can tell, the loose plan is to let it ring to its bell’s content, and when it eventually stops, that will be the day it gets opened up for investigation.

That day might never come. And then maybe no one will ever know.

And that just seems so weird to me. Except it’s kind of how everything else in the world works, too. Which is to say, everything basically runs, and no one has any clue how or why.

Nate Bargatze nails this same helpless feeling in his great bit about time travel.

It’s below, but the gist is that if Nate were to time-travel back to the 1920s, he’d be in a spot most of us would be. Namely, understanding that in the “future” there will be changes, but how those changes come about would be nearly impossible to explain.

His punchline, which comes at the beginning of the joke: “If I went back in time, knowing everything I know now, I don’t think I’d make a difference...I don’t think I could prove I’m from the future.”

Bargatze is saying here what we all know about ourselves. We live in a world with tons and tons of stuff (mostly kind of “basic”), and kind of no clue at all about how any of it gets done.

Sometimes it’s “easy” to see with the Oxford Electric Bell hidden behind a glass case, waiting for the day it’s opened. But even then, with the battery in plain sight, it would still be a mystery.

But then take everything else. The computer I’m typing on. The phone. Those are obvious. I don’t have any idea how they work, but neither do you. Spare me an explanation.

Everything else? All a mystery.

From the super complex (Super Halogen Collider, SpaceX rockets, this baldheaded-hairy-chested human body) all the way down to the simplest things out there in the world. Figuring out how any of it really works amounts to nothing more than a fool’s errand.

The second you think you’ve figured out one piece, there’s another part (or a million) behind it. Turtles all the way down.

Back in 1958, Leonard Read published “I, Pencil” an essay about the free market and how humans cooperate in unseen ways. Cliff’s notes: no one out there can make a pencil all on their own.

It takes complexity and systems well beyond what many would grasp when holding, writing, and filling in a Scantron with the old #2.

But between the wood, graphite, metal, rubber, paint, glue, machinery, and labor, it takes thousands and thousands of people spread across many countries to make a damn pencil.

Do we know how a pencil works? Maybe, at least from an outcome level. Do we understand how it’s made? Sort of, not really.

Bargatze’s understanding of his Marty McFly version of ignorance with how the world works is the comedic version of Read’s pencil version, and the written version of my least favorite emoji:

🤷

It’s not worth ripping open the Oxford Electric Bell for the answer about how it chimes, because it really won’t answer anything anyway.

The world is so freaking complex to try and distill it into its component parts, and operating systems is like me explaining the swivel chair I’m sitting on. It’s a chair, but man, is it ever so much more.

We have to treat the complex as simple, basically because we have no choice. I don’t know how [insert any very simple thing here] works, and I’m unlikely to ever understand because there’s always one more thread to pull, one more aspect to consider.

Which, in a lot of ways, is kind of freeing. Right? Or it’s an enormous cop out. One or the other.

The world is impossibly complex. But because it all is, none of it really is. Complexity collapses into simplicity.

No idea how the Oxford Electric Bell works. Also, no idea how my stove or blender works either, and I still make toast, fried eggs, and a watermelon smoothie every morning.

It’s fine to stick things behind the glass, shrug our shoulders, and just be like “I’m glad it turns on, even if how it turns on is anyone’s guess.”

And when we travel back in time to explain it to someone from the past, the easiest answer is something like:

“I’m not exactly sure what’s going on, but you’ll probably like it.”